Feb 17, 2015

John Canemaker reveals the secrets of the Fantasia Sweatbox Notes

Last fall, HowardLowery.com, the animation art auction site, offered collectors a chance to bid on a most unusual item. The particulars read: “Disney FANTASIA 10 Typed Sheets of SWEATBOX NOTES on ARAB DANCE to animator SANDY STROTHERS, 1940.”

When bidding closed on November 15, 2014, the item sold for only $67.00. Because it was not an original animation drawing or an inked and painted celluloid of a beloved cartoon character or a book autographed by Walt Disney, potential buyers were few and the bids low.

But I believe whoever acquired the item knew and appreciated its true value.

More than a mere sheaf of typewritten papers, vintage “sweatbox notes” are time-tripping portals into an early period in animation history that is arguably the Disney Studio's greatest, most innovative era.

The term “Sweatbox” was coined in the 1930s at the Disney Hyperion Avenue studio in Hollywood to described “[a] small projection room in which films are run for criticism,” wrote Bob Thomas in The Art of Animation, “so named in the early cartoon days before air conditioning.”1

In fact, it was a stressful examination room where animators literally sweat (even in the later air conditioned Disney Burbank studio) as their scenes were frankly dissected and discussed by Walt Disney and his film supervisors/directors.

Comments recorded by a stenographer were typed and distributed to all participants. The notes were marching orders from generals to troops in the trenches.

The day-by-day nitty-gritty creation of feature-length masterworks, such as Fantasia (1940), are embedded in these explicit, exacting papers. Clearly seen is the chain of command, deadline pressures, and the many details demanded of the artists and artisans who toiled together on a huge, complex, finely-tuned production line.

The recently auctioned notes deal with a few brief but mesmerizing scenes in Fantasia. “The scenes of the glowing white fish in the Arabian Dance section of 'Nutcracker Suite' amazed the whole Studio,” wrote Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston in Disney Animation: The Illusion of Life. “Never has an object on celluloid looked so diaphanous and delicate . . . No one had ever seen such a gossamer effect and very few knew how it had been achieved . . ..”2

Fantasia's fish ballet sequence, animated to Tchaikovsky's sensual music, is comprised of ten scenes running approximately three minutes on the screen. It required months of coordination between several departments, including Story, Character Model, Layout, Animation, Ink and Paint, Backgrounds, and Multiplane Camera, among others.

The auctioned sweatbox notes deal specifically with the animation of the seductive fish and special effects (bubbles, sparkles, languid kelp, etc.) in four scenes, particularly Scene 23 which runs for 112 feet on the screen, a little over one minute or 1/3rd of the total sequence.

Scene 23 was extensive in screen time and the amount of animation drawings (later transferred to cels), included constantly undulating fish, myriad bubbles, sparkles and other effects. The stack of artwork for this technical and artistic tour de force was “taller than one person could carry to the Camera Department.”3

Scene 23 is divided into three sections:

Don Lusk, who celebrated his 101th birthday on October 28, 2014, was the solo character animator of the piscine prima ballerina, a glowing white koi (“brocaded carp”). She and other fish “dancers” resemble Cleo, Geppetto's pet goldfish, a character Lusk had recently animated in Pinocchio (1940).

They retain a similar design: large disembodied heads with enormous, half-lidded, goo-goo eyes, long eyelashes and pouty lips. But the balletic white fish and her trio of black back-up dancers have absurdly long tail (caudal) fins.

Although they are called ballerinas, the intended effect is that of a sultry, heavily veiled Middle Eastern belly dancer, minus the belly. In fact, a belly dancer was hired as visual reference for the sequence, according to The Bulletin, Disney's in-house newsletter.5

The direction for the harem stereotypes in the sequence was set by Walt Disney himself: “You've seen travelogues where they take you into a harem,” he told the story artists.

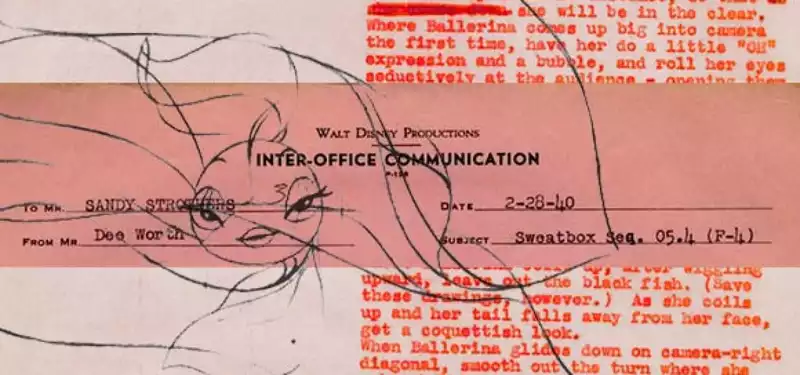

The first sweatbox note regarding Scene 23, on pink Inter-Office Communication paper dated February 28, 1940, is to Lusk. The instructions, probably written by “Nutcracker Suite” sequence director Samuel Armstrong after reviewing a screening of pencil tests with Disney, conveys the requisite “hootchy-koochy” the boss demands:

The sweatbox instructions suggest another possible inspiration: the very white and campy seductress Mae West. She of the orgasmic “Ohhh!,” seductive eye-rolls, and definitive “kootch wiggle,” vividly demonstrated when Mae and her two black maids go truckin', shimmying and singing “I Found a New Way to Go to Town” in I'm No Angel (1933).

Whatever inspiration was channeled, Lusk delivered and then some. His flowing, sensual fish dancers (animated “on ones,” e.g., twenty-four sequential drawings per second of screen time) are amazingly smooth in their non-stop undulations, and three-dimensional in the dynamic, complex staging of the scene. The moving imagery is both absurd and hypnotic.

The auctioned sweatbox notes were primarily directed to (and came from the collection of) Sandford (Sandy) Strothers (1904-1985), a hand-drawn special effects animator, who in this case focused on choreography of the sequence's hundreds of tiny bubbles, sparkles and “scintillation” effects.7 (The latter effect may refer to either flashes of highlights on some fish's scales or background sparkles.)

At the end of the February 28 note to Lusk are specific requests of Strothers, the lead effects animator for the sequences:

An April 9, 1940 sweatbox note to Strothers demands: “We want this scintillation animation put on two's.” [Two frames per drawing.]

To keep everyone on the same page and in the loop-and to make sure everyone does exactly what the director and Walt Disney want-this particular sweatbox note also addresses the scene's checker (“We will have loop tests made for both Lusk and Strothers, to be checked by Music Room…”) and layout man Zinnen (“Strothers will check with you on shooting of next scintillation test, and use of truck and light-beam mask.”) The Disney Studio production assembly line was tightly controlled with extensive checks and balances from the top creative execs (starting with Walt) on down.

Even assistant effects animators received pithy orders. John F. Reed, for example, was told in an April 13 note: “Take out the jerks on right-hand and left-hand sides of the seaweed. Watch hookup of the cycle on the fish. Check all inbetweens.”

Five days later, another note again zeros in again on Reed and the troublesome seaweed: “Correct action of right-hand weed per discussion…There is a quick return in its action that needs to be smoothed out.”

Reed was used in various Fantasia segments, e.g., animating dewdrops and ice designs also in the Nutcracker Suite; a centaurette's veil in the Pastoral Symphony; ghosts, flying goblins, smoke and flames in Night on Bald Mountain scenes. Some years after leaving Disney, he became animation director for Britain's 1954 animated feature Animal Farm, based on the George Orwell novel. “Reed's influence on the animation in Animal Farm was tremendous,” recalled an Animal Farm colleague. “He knew exactly the effect he wanted and how to get it.”8

In the final sweatbox note dated July 19, the complete Scene 23 was “O.K. for final check.” Except for one more addition requested of Strothers:

Most impressive to me regarding the revelations of sweatbox notes is the amount of attention paid even to the smallest element of each scene in the feature cartoons. The coordination of so many departments doing so many technical and artistic functions demanded nit-picking and control freaks all the way down the line. The result is this case is a fascinating few minutes of dream-like movement and color.

What does master animator Don Lusk think of his now-famous section of the legendary Fantasia-

“We were rushed for time,” Lusk recently told Steve Hulett. “At the premiere I practically crawled underneath the seats, it was so bad!”9

The “it” Lusk refers to were attempts by the director and the Ink and Paint and Camera Departments to bring filmy transparency to the languid fish tails and a glowing radiance to the fish dancers. “My only suggestion was that they shoot it twice, once at say 50%, then 100%, so the tails you could see through them,” recalled the only surviving participant in the creative process for Fantasia's fish ballet sequence.

Multiple camera passes using masking for lighting effects, airbrush and other technical methods were utilized. But the decision that still rankles Lusk after seventy-five years was the use of dry brush on the fish.

Don Lusk was born on October 28, 1913 and started his career at Disney in 1933, working there (except for the 1941 employees strike and World War II military service) till 1960 on thirteen features, from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs to One Hundred and One Dalmatians. Last month, he was honored with a Winsor McCay Award at ASIFA-Hollywood's Annie Awards celebration, in recognition of his career contributions to the art of animation.

What you are hearing in the veteran animator's astringent, unsentimental comments above is really an echo from the past. His words are a direct reverberation of Walt Disney's voice and creative spirit, and his still-inspiring drive for perfectionism and artistry in animation.

NOTES

1. Bob Thomas, Walt Disney-The Art of Animation. New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc. 1958, pp. 181 & 98.?

2. Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston, Disney Animation-The Illusion of Life. New York: Abbeville Press, p. 274.?

3. John Culhane, Walt Disney's Fantasia. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1983, p. 60.?

4. Fantasia Animation Work Draft, 8/19/40, p. 18.?

5. The Bulletin Fantasia Edition, 15 November 1940, p. 2+.?

6. Culhane, p. 61.?

7. Thanks to Joe Campana for Strothers' birth/death dates.?

8. Vivien Halas and Paul Wells, Halas & Batchelor Cartoons – An Animated History. London: Southbank Publishing, 2006, p. 142.?

9. Don Lusk interview by Steve Hulett, 30 October 2013. http://animationguildblog.blogspot.com/2013/10/the-don-lusk-birthday-interview-part-iii.html – Oct. 30, 2013.?

JOHN CANEMAKER is an Academy Award–, Emmy Award–, and Peabody Award–winning animation director and designer. His twenty-eight minute film, The Moon and the Son: An Imagined Conversation, won the 2005 Oscar for Best Animated Short, and his more than twenty films (and their original art) are in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. He has written eleven books on the history of animation. He is also a tenured professor and director of the animation program at New York University's Tisch School of the Arts. Visit his website at JohnCanemaker.com.

Post your comment